Incense, Painting & Self-Cultivation: The Way of Eastern Aesthetic Life

Introduction

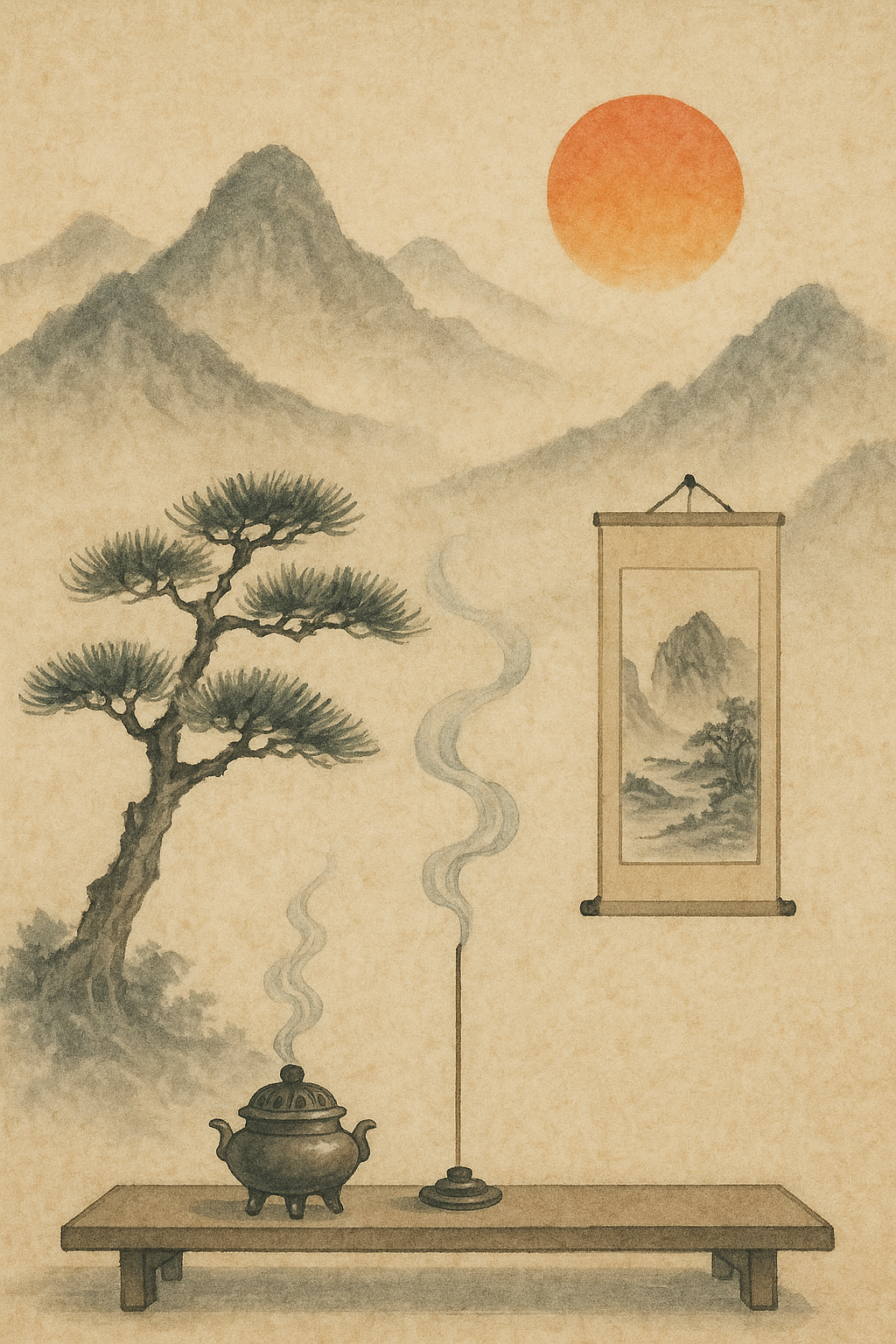

To some, Eastern tradition may feel distant or decorative. But for those who light incense at the tea table, smooth ink over white paper, or read lines of poetry quietly, incense, painting, and self-cultivation are not antiquated rituals, but daily moments of dialogue—with ourselves, with nature, and with the spirit. There is no pretense, only a gentle rhythm and the echoing voice of the inner world.

Incense: The Bridge of Smoke and Spirit

China’s incense culture can be traced back to the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), where incense was not only used in rituals but also to fragrance rooms and fabrics.

By the Tang dynasty, exotic aromatics such as sandalwood, agarwood, and frankincense had gained favor among the imperial court—used in incense burners, bathing rituals, and fragrant sachets.

From the Song dynasty onward, Xiangdao, the “Way of Incense,” became a cultivated art among literati, often placed alongside tea, flowers, and painting.

When we light incense, the curling smoke becomes a bridge between human and heaven. It carries scent, thoughts, prayers — an invisible language that drifts into every corner of the space.

Appreciating Paintings: Landscape of the Heart

Literati painting (wenrenhua) emphasizes “spirit over likeness.” The style crystallized during the Northern Song dynasty and became a leading artistic approach in later dynasties.

Rather than focusing on realistic representation, literati paintings prize the brush, the spaces left blank (liubai), and the emotional resonance embedded in the work.

In classical times, scholars in gardens or studios would unfurl scrolls and mentally wander through their landscapes. When smoke from incense mingled, mountains, bamboo, plum blossoms became interlocutors—light and shade dancing as reflections of mind meeting nature.

Self-Cultivation: From Outer Ritual to Inner Growth

Cultivating the self is central to Eastern thought. The classic Great Learning (Daxue) begins: “Cultivate the self, regulate the family, govern the state, bring peace to the world.”

In daily life, scholars balanced their spirit by incense to adjust qi, paintings to nourish the mind, and poetry or calligraphy to accompany the hours. These seem slow, but they steady the heart and make time feel intimate.

In our fast-paced era, these old ways are not outdated—they are a gentle resistance. Rituals that allow us to slow down, breathe, and in every waft of smoke, every brushstroke, return to ourselves.

Conclusion

Incense, painting, and self-cultivation are not separate acts, but threads woven through a life. Incense opens the window to silence, ink places emotion on paper, and self-cultivation gives the heart a resting place. If you light a stick of incense each day, unroll a scroll, and let yourself breathe gently through time—you begin your own Way of Eastern life.